Hormones react to clothing faster than thoughts do. Before we put our state into words, the body has already received signals from fabrics, weight, silhouettes, and colours — and adjusts mood, energy, and our ability to stay present in the day. Style becomes not an external image but a way to influence our own biochemistry.

In the first article “What the body feels in clothes” we explored sensory perception: how fabrics, weight, and silhouettes work with the nervous system. Here — we go further. We examine how these bodily signals influence hormones: cortisol, dopamine, oxytocin, serotonin, and melatonin. Read more on seasonal hormonal shifts in the third article of the series — “Seasons and motion”.

Hormones as the internal language of style

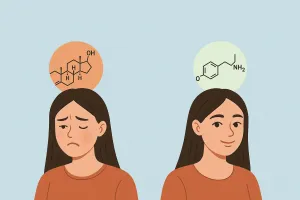

Hormones shape our daily states: stability, mood, motivation, and our ability to recover. We rarely connect this to style — and yet clothing influences the hormonal system as much as light, temperature, or social interaction.

When fabric touches the skin, when a silhouette defines the body’s boundaries, when colour interacts with surrounding light — the brain receives immediate signals. Some soothe. Others activate. Others motivate. This is how style becomes a biochemical practice.

Cortisol: when style calms and when it activates

Cortisol is the stress hormone, but also our main “morning engine”. It provides clarity, focus, and tone. The issue is not cortisol itself but its excess or deficiency. Clothing can affect both states.

When style lowers cortisol

The body calms when:

- fabric is soft, warm, or evenly dense;

- the silhouette does not restrict breathing;

- the weight of clothing provides deep pressure;

- colour does not overstimulate;

- sensation on the skin feels predictable.

You can feel it literally: a heavy cardigan on a difficult day, soft cotton in the evening, cashmere that “embraces” your shoulders. The body calms down before we even name the feeling.

When style activates cortisol “in a healthy plus”

There are moments when softness does not help. Then we need tone. Structured shoulders, dense fabrics, clear silhouettes — can raise cortisol to a clarity level: gather, focus, restore mobility.

This is the moment when we put on a blazer and feel our thoughts aligning, movements sharpening, attention returning. This is not an “image effect”. This is biochemistry.

Dopamine: the hormone of anticipation, novelty, and inner movement

Dopamine is not about joy. It is about direction. About “pulling forward”. Novelty, symbols of growth, small challenges, role changes — and clothing can send all these signals.

Dopamine increases when:

- we put on something new or wear familiar clothes in a new way;

- the silhouette shifts posture and mood;

- colour creates a spark of anticipation;

- texture gives tactile pleasure;

- the look is associated with moving forward.

This explains the phenomenon when a “new piece” changes emotions within seconds. The brain reacts not to aesthetics but to new potential.

In the article Dopamine dressing: how clothing influences motivation, choice, and inner movement we explore the difference between a dopamine spike and dopamine stability — and why sometimes we need not new things but those that remind us of steadiness.

Colour: soft hormonal modulation

Colour affects hormones through light. Light → retina → hypothalamus → hormonal regulation. This is not a metaphor but direct neurophysiology.

Blue and green calm by lowering sympathetic activation. Yellow and coral stimulate dopamine anticipation. Earth tones create a feeling of stability. Dark fabrics in winter support inner collectedness. Bright cool colours in summer act as a light serotonin stimulus.

Read more in the article Colour as soft neurotherapy.

Oxytocin: warmth, softness, and social trust

Oxytocin is the hormone responsible for trust, empathy, and feelings of safety. Soft fabrics, deep pressure, fitted knitwear, warm blankets — all stimulate oxytocin pathways. It is similar to a “non-verbal touch”.

There is a social aspect: in soft fabrics we are more open to interaction; in structured ones — we maintain boundaries better. Clothing becomes a tool for regulating social energy.

Melatonin and circadian rhythms: why light and seasonality matter

Melatonin is sensitive to light and colour. Thus summer and winter styles are not just about aesthetics but the brain’s reaction to illumination.

Bright light signals the brain to stay active — hence light fabrics, bright colours, cool textures feel natural. In winter darkness the body asks for warmth, weight, texture, oxytocin.

Why “nothing to wear” happens: hormonal dissonance of choice

This state is not about the wardrobe — it is about the brain failing to find something that balances the hormonal landscape:

- lowers cortisol,

- supports oxytocin,

- adds a touch of dopamine novelty,

- stabilises emotional reactivity.

More about this — in the biochemistry of choice: why we have nothing to wear.

Internal coherence: when style and hormones work together

Ideal style is not about the look but the state: when fabric does not “make noise”; when colour matches the light of day; when the silhouette holds or releases exactly as needed; when weight stabilises, and novelty inspires. That is the moment when style works with biochemistry, not against it.

This is inner presence — the state where we do not “put on a role” but return to the body.

Sources

- McEwen, B. S. (2007). Physiology and neurobiology of stress and adaptation: central role of the brain. Physiological Reviews. URL: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17615391/

- Adam, H., & Galinsky, A. D. (2012). Enclothed cognition. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. URL: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0022103112000200

- Salamone, J. D., & Correa, M. (2012). The mysterious motivational functions of mesolimbic dopamine. Neuron. URL: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22958817/

- Elliot, A. J., & Maier, M. A. (2014). Color psychology: effects of perceiving color on psychological functioning. Annual Review of Psychology. URL: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23808984/

- Porges, S. W. (2011). The Polyvagal Theory. Norton. URL: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3108032/