A child is not born with a finished emotional system. They are born with neural tissue that seeks contact. And the first signal for this system is—the face. In it the child “reads” the world: safety, warmth, interest, fear, calm. A parent’s facial expressions are the child’s first dictionary of feelings.

A language without words

Before a child starts to speak, they already “talk” with their eyes, facial muscles, and hand movements. They don’t understand the meaning of the word “joy,” but they recognize it in the gaze, tone of voice, and shape of a smile. This is a primary neuronal dialogue—an emotional synchrony that builds trust in the world.

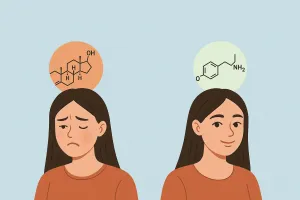

Psychologists call this emotional resonance. When a mother smiles and looks with tenderness, the same brain regions activate in the child as in her. The body seems to respond, to mirror, to learn through imitation. This is where the story of empathy begins.

Mirror neurons: how the brain “feels” others’ emotions

In the 1990s, Italian neurophysiologist Giacomo Rizzolatti discovered mirror neurons—brain cells that fire not only when we act, but also when we watch someone else act. So when a child observes a smile, they feel it inside themselves.

This discovery reshaped our understanding of how social skills develop. Mirror neurons provide a biological basis for empathy—they let us “experience” another’s state without words. As Marco Iacoboni writes in Nature Reviews Neuroscience (2009):

“Mirror neurons enable understanding of actions and emotions through internal simulation.”

And this explains why children are so sensitive to their parents’ moods. When a mother is tired or tense, even if she says nothing, the child feels it with their body.

First lessons in emotional intelligence

In the first months, small things decide everything: how we respond to crying, how we hold a baby, how we meet their eyes. When an adult responds gently and consistently, a neural template of safety is reinforced in the child’s brain. This is the first experience of self-regulation: “I can get upset—and return to calm again.”

Lack of eye contact, indifference, or a chronically tense face from an adult becomes “noise” in communication. The child doesn’t know the reasons, but their nervous system gets the signal: the world is unpredictable. That’s why even a brief, warm gaze is an investment in future emotional balance.

A face that teaches

A parent’s face is a mirror in which a child sees not only themselves, but also the boundaries of the world. Through it they learn to recognize anger, joy, tenderness, calm. Empathy isn’t born in isolation—it grows from relationships.

Research from the Harvard Center on the Developing Child emphasizes:

“Consistent, emotionally attuned caregiving supports the architecture of the developing brain.”

When an adult’s face is steady, calm, and accepting, the child forms an inner anchor. Their brain learns that emotions are safe—something you can experience and release.

Mirror and play

Playing in front of a mirror is more than fun. It’s a first laboratory of emotions. When a mother mirrors her baby’s expressions, the child perceives: “I am understood.” When they laugh together, a neural bridge forms between body and feeling. These micro-moments lay the foundation of emotional literacy. And even as a child grows, a simple rule remains: explain emotions with your face—not only with words, but with your look, expression, and touch.

Practical guide: how to help a child learn emotions

- Meet eyes—every day. A few seconds of real contact three times a day (morning, after school, before bed) boosts oxytocin and a sense of safety.

- Mirror the emotion—while staying calm. “You’re angry right now, I see it. I’m here.” The child learns to recognize and tolerate feelings.

- Name feelings out loud. “You’re upset because you wanted it different,” “You’re happy because we’re together”—this builds an emotional vocabulary.

- Play the “emotional mirror.” First you show joy/surprise/calm—the child copies; then switch roles. This activates the brain’s mirror system.

- Body safety first, explanations second. Hugs, synchronized breathing, a soft voice—and only then the conversation.

- Fewer screens, more faces. Add “live minutes”: a gadget-free breakfast, 15 minutes of evening eye-to-eye talk.

How it works: this isn’t moralizing, it’s neural tuning. Children learn less from lectures and more from repeating an adult’s bodily responses. When they see a calm breath even in stress, their nervous system gradually learns to do the same.

When a screen replaces a face

Today children often look at images rather than people. They see bright emotions on a screen but don’t get live feedback—warmth, response, shared rhythm. Neuroscientists are already noting that excessive screen time lowers activity in the brain’s mirror system. Children who spend more time with gadgets are worse at recognizing real facial expressions.

That’s why even five daily minutes “without screens,” when parents simply look their child in the eyes, is powerful empathy training.

Return to the face

Emotional literacy isn’t learned from books. It grows in the body—through gaze, touch, shared laughter. Every expression we show is a small message: “I see you. I’m with you.” In that simple phrase lives the pedagogy of love. When a child feels seen, they don’t fear the world. They learn the essential skill—to feel others without losing themselves. And that is true emotional maturity.