We often drink green tea to wake up. But if you look closely at its chemistry, it becomes clear: this drink is less about stimulation and more about balance. In the Japanese tea tradition, brewing is an act of contemplation, not acceleration. And while we keep asking whether green tea raises or lowers blood pressure, science speaks about something else entirely — harmony between nerves, vessels, and the heart.

The Chemistry of Calm: What’s Inside the Cup

Green tea contains over 200 active compounds, but three of them define its physiological effects:

- Catechins (EGCG) — potent antioxidants that improve vascular elasticity and stimulate nitric oxide production, helping arteries relax.

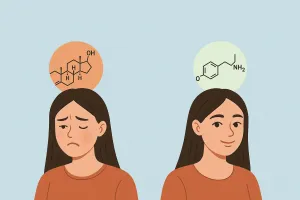

- Teine (caffeine) — a natural stimulant that increases heart rate and can transiently raise blood pressure.

- L-theanine — an amino acid that counterbalances caffeine: it relaxes, reduces anxiety, and supports focused attention without tension.

Together they create a unique balance — green tea both energizes and soothes. It’s a “soft conflict” between adrenaline and meditation, between a quickened heart and a slower mind.

How Green Tea Affects Blood Pressure

In the first 30 minutes after a cup, most people experience a short-lived increase of about 3–5 mmHg — the effect of caffeine on the sympathetic nervous system. Then catechins come into play: they stimulate endothelial cells to produce nitric oxide (NO), relaxing vessels and improving microcirculation.

Clinical studies (e.g., Journal of Hypertension, 2016; Nutrients, 2022) indicate that regular green tea intake over 8–12 weeks can reduce systolic pressure by about 2–4 mmHg — especially in people with mild hypertension. In other words, the effect is cumulative: short-term — a slight rise; long-term — stabilization.

What Science Shows: From Catechins to Genes

A meta-analysis in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition (2020) found that drinking three or more cups of green tea daily is associated with a lower risk of hypertension. At the same time, Frontiers in Nutrition (2018) highlights a genetic factor: variants of the caffeine-metabolizing enzyme CYP1A2 matter. Carriers of the “slow” variant may see a brief pressure increase, while “fast metabolizers” are more likely to experience a reduction.

So green tea does not act the same way for everyone. Its impact is a dialogue between our genes, our nerves, and the cup in our hands.

The Heart, the Brain, and Calm: Tea as a Neuromodulatory System

L-theanine increases levels of GABA as well as dopamine and serotonin — neurotransmitters linked to calm and satisfaction. That’s why green tea produces a state of “alert calm”: you wake up, but without strain.

As we discussed in “Mood Molecules: How Stress and Dopamine Affect Your Skin”, balance between neurotransmitters is key. Green tea works at the intersection of the nervous system and emotion: it dampens stress-driven vascular fluctuations and helps restore rhythm to breath and heart.

Who Should Drink It and How — for Different Blood Pressure Profiles

- For hypertension: 1–2 cups per day after meals, preferably morning or midday. Excess may raise pressure due to caffeine.

- For hypotension: morning cups can gently lift blood pressure and circulation.

- Caffeine-sensitive individuals: choose sencha or genmaicha, typically lower in caffeine.

Avoid taking green tea at the same time as antihypertensive medications — catechins may blunt their effect.

A Ritual That Lowers Pressure

The brewing itself has a therapeutic effect. Slow movements, the cup’s gentle warmth, the aroma — all this activates the parasympathetic nervous system, reducing heart rate and cortisol. It’s akin to breathing practices we wrote about in “When Calm Brings No Joy”.

- Steep at 70–80 °C rather than boiling — this preserves antioxidants.

- Drink slowly, noticing taste and breath.

- Listen to your body — do you feel warmer, is breathing easier?

Tea and Evening Harmony

There are caffeine-free green teas — for example, decaffeinated sencha or blends with lavender and jasmine. They can be suitable before bedtime. Polyphenols in such tea help regulate GABA and melatonin, improving sleep quality.

For more on the evening routine, see “Dinners for Better Sleep” — where every detail of the night menu influences hormones of calm.

The Symbolism of Tea and the Bodily Experience

In today’s fast tempo, green tea becomes not only a drink but also a ritual of returning to oneself. Like touch — which we explored in “How Much Touch the Body Needs” — a cup of tea is a form of gentleness: warmth the body recognizes as safety.

Blood pressure is not just a number on a monitor — it’s also how we react to the world. Green tea helps make that reaction softer.

Conclusion: Balance in a Cup

Green tea cannot be labeled simply as a stimulant or a sedative. Its power lies in balance. It teaches the body the subtle art of self-regulation: raising pressure to live — and lowering it not to burn out. Science explains mechanisms, but true calm is born not in a lab — it appears the moment we bring the cup to our lips and feel the world slow down.

-lazy-placeholder.webp)

-medium.webp)