Kako koristiti ovaj članak

Ovaj tekst nije uputa. Namijenjen je čitanju kao prostoru za promatranje sebe — bez potrebe da išta radite ili mijenjate.

Ako se tijekom čitanja pojavi prepoznavanje, tjelesna reakcija ili unutarnja pauza — to je već dovoljno. Izostanak reakcije također je normalan odgovor.

U danima kada nijedna kombinacija „ne funkcionira“, ovaj članak može biti ne savjet, nego dopuštenje da od sebe ništa ne tražite.

U razgovorima o odjeći često tražimo brz učinak: da „popravi raspoloženje“, „doda energiju“, „promijeni dan“. No tijelo ne reagira na odjevnu kombinaciju kao na ideju. Ono čita signale: pritisak tkanine na kožu, slobodu ili ograničenje pokreta, osjećaj topline, svjetla i boje. Zato odjeća rijetko „čini sretnima“, ali često utječe na nešto drugo — na spremnost da živimo, krećemo se, biramo i izlazimo u svijet.

Dopamine dressing često se objašnjava kroz jarke boje i „brze emocije“. No na razini neurofiziologije postaje jasno: ne radi se o radosti. Radi se o motivaciji. Ne o učinku, nego o procesu — o unutarnjem pokretu koji ponekad započinje vrlo tiho.

U tom smislu, odjeća prestaje biti sredstvo samoistražavanja i postaje dijalog. Ne odgovara na pitanje „kako izgledam“, nego sugerira nešto drugo: je li tijelo spremno napraviti korak naprijed ili mu je potrebna pauza.

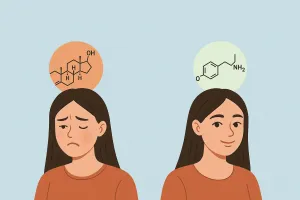

Dopamin je hormon iščekivanja, a ne užitka

U popularnoj kulturi dopamin se često naziva „hormonom sreće“, no to pojednostavljenje može zavesti. Dopamin je neurotransmiter iščekivanja, očekivanja i motivacije. Aktivira se ne onda kada se već osjećamo dobro, nego kada se pojavi osjećaj: „nešto je moguće“, „ima smisla krenuti“, „spreman sam napraviti korak“.

S neurofiziološkog gledišta, dopamin sudjeluje u izboru, iniciranju radnje i usmjeravanju pažnje. Zato je usko povezan s načinom na koji biramo odjeću. Čak i automatski jutarnji izbor šalje signal živčanom sustavu: danas sam sabran ili opušten, zaštićen ili otvoren, usmjeren na djelovanje ili na oporavak.

Važno je razlikovati dopamin od serotonina. Serotonin je povezan sa stabilnošću i osjećajem „dovoljno je“. Dopamin je povezan s impulsom prema naprijed. Kada od odjeće očekujemo smirenje, a nalazimo se u fazi traženja pokreta, nastaje unutarnji nesklad.

Ponekad se to osjeti vrlo jednostavno: odjeća izgleda „ispravno“, ali u njoj se ne želi izaći iz kuće.

Širi kontekst odnosa hormona i stila obrađen je u članku Moda i hormoni: kako stil regulira kortizol i dopamin, gdje se odjeća promatra ne kao dekoracija, nego kao dio sustava regulacije stanja.

Dopamine dressing kao strategija kontakta sa životom

Kada se odreknemo ideje da odjeća mora „popraviti raspoloženje“, dopamine dressing počinje djelovati drukčije. To nije stimulacija niti pokušaj da se prisilimo na aktivnost. To je način da provjerimo je li tijelo spremno na minimalni pokret.

U praktičnom smislu korisno je obratiti pažnju ne na izgled, nego na tjelesnu reakciju. Mijenja li se disanje? Postoji li želja da se hoda malo brže — ili, naprotiv, da se uspori bez napetosti? Pojavljuje li se osjećaj unutarnjeg oslonca — ne kroz kontrolu, nego kroz stabilnost?

Ponekad taj signal dolazi iz jednog detalja. Ne iz cijele kombinacije ili koncepta, nego iz male tjelesne suglasnosti: „da, u ovome se mogu kretati“. Drugim danima nijedan komad ne izaziva reakciju — i to je također odgovor, a ne pogreška.

Što nije dopaminska odjeća — i što češće pokreće kretanje

Postoje komadi koji izgledaju uvjerljivo, ali ostavljaju tijelo nepomičnim. „Ispravna“ odjeća, savršeno osmišljene kombinacije, komadi koji zahtijevaju držanje posture ili stalnu samokontrolu — sve to može stvoriti dojam sabranosti, ali ne i potaknuti impuls za djelovanje. Dopamin ne reagira na ispravnost. On reagira na mogućnost.

Odjeća „za dojam“ također rijetko djeluje — ona koja traži pažnju, provjeravanje u ogledalu i vanjsku potvrdu. U takvim kombinacijama tijelo se obično napinje: disanje postaje pliće, ramena se podižu, kretanje usporava. To može nalikovati uzbuđenju, ali je bliže napetosti nego motivaciji.

Najčešće dopaminski „starter“ nije cijela kombinacija, nego jedan živ detalj. Komad u kojem se želi hodati malo brže. Tkanina u kojoj je disanje slobodnije. Oblik koji daje osjećaj „mogu se kretati u ovome“. To nije stvar jarkosti ili hrabrosti — riječ je o mikro-novosti koju tijelo doživljava kao sigurnu.

Paradoksalno, dopamin se češće aktivira kada kombinacija nije u potpunosti dovršena. Kada postoji prostor za izbor: zakopčati ili otkopčati, podvrnuti, prilagoditi kroj. U tim trenucima pojavljuje se osjećaj agencije — „mogu“ — koji je u samoj srži motivacije.

Dopaminska odjeća nije ona u kojoj se osjećamo dobro. To je ona u kojoj je nešto moguće. Korak, pokret, odluka, izlazak u svijet. Ponekad vrlo malen — ali dovoljan da se život ponovno pokrene.

Senzorna osnova: zašto dopamin ne funkcionira bez nje

Nijedna dopaminska aktivacija nije moguća bez osnovnog osjećaja sigurnosti. Živčani sustav ne ulaže energiju u iščekivanje i kretanje ako je tijelu neugodno. Zato senzorne karakteristike odjeće — tkanina, šavovi, težina, temperatura — imaju mnogo veću važnost od usklađenosti s modnim kodovima.

Za živčani sustav, ugoda nije „udobnost“, nego signal da se kontrola može smanjiti. Kada odjeća ne pritišće, ne grebe i ne zahtijeva stalno namještanje, tijelo oslobađa resurse za izbor, pažnju i motivaciju.

Ovo je načelo u središtu pristupa opisanog u članku Senzorna osnovna garderoba: kako odjeća smiruje živčani sustav i podržava unutarnju stabilnost, gdje se garderoba promatra kao senzorna potpora, a ne vizualni konstrukt.

Dopamine dressing ne počinje bojom ili imidžem. Počinje tjelesnom sigurnošću.

Kada dopamine dressing ne djeluje — i to je normalno

Postoje razdoblja kada nijedna odjeća ne izaziva reakciju. Pojavljuje se osjećaj „nemam što obući“, iako je garderoba objektivno puna. U tim trenucima lako je početi kriviti sebe — no to samo povećava napetost.

Kronični stres, emocionalna iscrpljenost i preopterećenje izborima smanjuju osjetljivost na dopamin. Tijelo prestaje vidjeti smisao u malim odlukama. Uz to dolaze frustracija, apatija i osjećaj „sa mnom nešto nije u redu“.

U stvarnosti, to nije kvar. To je pauza.

Biokemija izbora: zašto se ponekad javlja „nemam što obući“

U takvim danima pojednostavljenje djeluje bolje od traženja. Povratak poznatim komadima nije odustajanje od stila, nego način da se živčanom sustavu dopusti oporavak.

Sezonalnost i spremnost na novost

Spremnost na djelovanje ne mijenja se samo kroz unutarnje procese, nego i kroz sezonske signale koje tijelo automatski očitava. Jutarnje svjetlo koje ulazi u oči, dulji dani, topliji zrak — sve to postupno mijenja cirkadijalne ritmove i izvodi živčani sustav iz načina štednje.

U proljeće mnogi primjećuju jednostavne promjene: lakše buđenje, želju za izlaskom iz kuće bez jasnog cilja, promjenu tempa hoda. To nije emocionalni uzlet niti inspiracija — to je fiziološka spremnost za mikro-pokrete. U takvom stanju dopaminske petlje aktiviraju se lakše, bez prisile.

U tom razdoblju odjeća često počinje „djelovati“ drukčije. Ono što je zimi bilo neutralno odjednom se osjeća kao poziv. Ne na radikalnu promjenu, nego na oprezno eksperimentiranje: dužu šetnju, drukčiju rutu, dopuštanje male novosti bez obveze.

Proljetno buđenje kroz odjeću: kako sezona mijenja tjelesnu spremnost za novost

Ne više emocija, nego više živosti

Dopamine dressing nije o tome da se osjećamo bolje pod svaku cijenu. Niti o tome da se silom izvlačimo iz pauze. Njegov je smisao u podršci unutarnjem pokretu ondje gdje je moguć — i u pažnji prema trenucima kada pokret još nije dostupan.

Ponekad odjeća postaje početna točka: u njoj se želi izaći, hodati, započeti. Ponekad je tihi okvir koji dopušta da od sebe ne tražimo previše. U oba slučaja, ona ne djeluje kao rješenje, nego kao signal — je li tijelo sada spremno na korak.

Možda je ovdje najtočnije pitanje ne „što da obučem“, nego „što mi je sada moguće“. I ako je odgovor vrlo malen — i to je kretanje. Upravo se iz takvih suptilnih, gotovo neprimjetnih pomaka gradi živost.

Izvori

- Berridge K. C., Robinson T. E. What is the role of dopamine in reward: hedonic impact, reward learning, or incentive salience? Brain Research Reviews.

- Salamone J. D., Correa M. The mysterious motivational functions of mesolimbic dopamine. Neuron. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2012.10.021

- Damasio A. The Feeling of What Happens: Body and Emotion in the Making of Consciousness. Harcourt Brace & Company.

- Craig A. D. How do you feel? Interoception: the sense of the physiological condition of the body. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn894

- McEwen B. S. Protective and damaging effects of stress mediators. New England Journal of Medicine.

- Cajochen C., Kräuchi K., Wirz-Justice A. Role of melatonin in the regulation of human circadian rhythms. Journal of Neuroendocrinology.