If, during intimacy, you suddenly catch yourself thinking “how do I look right now?”—that’s not “silly” and not a “whim”. It’s a sign that your attention has shifted into control rather than sensation. And then, even with a loved one, the body may remain tense, desire—unstable, and pleasure—as if nearby, but not inside.

In this article, we talk about how body dissatisfaction and shame affect libido, arousal, and the feeling of closeness. Without moralizing, without “just love yourself”, without descriptions of intimate practices. Only about the nervous system, attention, safety, and small steps that help you return to contact with yourself.

If you need the bigger picture—how stress and “survival mode” affect desire—see “Stress, anxiety and sex: why desire disappears when we’re tired”. And to understand the basics—how arousal works from the perspective of the nervous system—it helps to keep the pillar article “Sex, the nervous system and intimacy” at hand.

Why am I ashamed to undress in front of my partner, and what can I do about it?

Body shame rarely appears “out of nowhere”. It grows from experiences of comparison, criticism, other people’s looks, comments about weight, skin, age, “ideal” proportions. Even if your partner says nothing bad, the brain may hold on to an old rule: “don’t show yourself like that, it’s dangerous”.

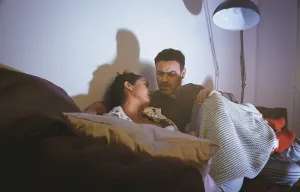

Mini-scene. You walk into the bedroom; the light is brighter than you’d like. Your partner reaches out to hug you, and your stomach tightens automatically, your shoulders tense, and a thought appears: “just don’t let it show…”. This isn’t a “bad mood”. It’s the nervous system’s signal: “I’m being judged”.

In intimacy, the body needs a sense of safety. When the signal “I’m being judged” is on, the nervous system switches into control: we monitor posture, light, “can they see my stomach”, “does my skin look like that”, “am I attractive enough”. This isn’t about desire. It’s about self-protection.

The first step is not to force yourself to “stop being ashamed”, but to admit: “this is how it is for me right now”. Next—create conditions where safety is more real than evaluation: softer light, a slower pace, more pauses, clothing you feel calmer in. These aren’t “quirks”. It’s care for connection.

How can I relax during sex if I keep thinking about my body?

When, during sex, you keep thinking about your body, attention splits: one part of you is in sensations, and another—in control of “how do I look”. In that state, it’s hard to feel arousal deeply: the nervous system is busy evaluating, not connecting.

Importantly, the goal is not to “turn off thoughts by force”. The goal is to give the body a safety signal and bring attention back to the present moment.

How to return to your body in 30 seconds?

- 3 sensations: name three sensations in your body (warmth, pressure, touch, pulse, support).

- 2 anchors: find two points of support in space (back on a pillow, feet on the sheet, a palm on the blanket).

- 1 exhale: take one exhale slightly longer than the inhale (without effort).

This is a simple way to return from evaluation to sensation. Even if shame doesn’t disappear right away, tension often drops, and connection becomes closer.

What if the inner critic hits?

When “I’m not like that” appears in your head, don’t argue with it for long. Give a short anchor response and return to your body:

- “I’m allowed to be alive, not a picture.”

- “I’m coming back to sensation.”

- “My body has a right to comfort.”

What can I do if I’m insecure about my belly/stretch marks/cellulite?

Insecurity about your belly, stretch marks, or cellulite can look like a small thing only “from the outside”. Inside, it can be a strong shame trigger: “they’ll see me and turn away”, “I’m not enough”, “I’ll ruin the moment”. And then the body tightens, breathing becomes shallow, and arousal is harder to access.

Here, the principle “comfort matters more than the image” works. You have a right to conditions that feel safer: dimmer light, a favorite T-shirt, a blanket, more time for cuddling, a slower pace, a pause at any moment. This isn’t “playing into shame”. It’s a way to help the nervous system step out of control.

Which comfort options to choose if your partner is nearby or if you’re alone?

- If your partner is nearby: ask for one simple thing (pace, light, pause) and take 2–3 slow exhales together.

- If you’re alone: return body sensation through warmth and support (shower, blanket, warm drink, soft fabric), without evaluating yourself in the mirror.

Why does desire disappear when I don’t like myself?

Desire is often born not from an “ideal shape”, but from a combination of safety, trust, and resources. When resources are low (fatigue, lack of sleep, stress), and self-criticism is also running, the sexual system responds logically: “not now”. Instead of “I want”, “I must match” appears.

Mini-scene. The day was hard, your head is full of to-dos, your body is tired. Your partner shows tenderness, and you kind of want it, but inside it sounds like: “I’m not in shape right now”, “I’m not attractive”, “I should look better”. This isn’t a lack of feelings. It’s overload and the pressure to “measure up”.

Self-dissatisfaction increases tension even in pleasant situations. And where there is tension, playfulness and spontaneity often disappear. If you notice that lack of sleep is also a strong theme, it can help to keep in focus the guide “How to restore your sleep and calm your nervous system: evening habits, night rest and morning rituals”, because sleep and libido often draw on the same resources.

Which myths about the body and sex get in the way the most?

- Myth: “First you have to love yourself, then sex will be good.” Reality: sometimes body neutrality is enough—not worshiping yourself, but respecting yourself and not attacking yourself with words.

- Myth: “If I’m ashamed, it means I don’t want my partner.” Reality: shame is often about safety, experience, and the habit of controlling yourself—not about love.

- Myth: “If I think about my appearance during sex, something is wrong with me.” Reality: it’s a common control mode that can be gently reset through attention and body anchors.

- Myth: “Self-care or weight loss will fix everything.” Reality: what helps is what adds comfort and safety—not what turns into punishment and pressure.

Why do “glossy scripts” get in the way of desire in real life?

There’s a paradox: the more “ideal” bodies and “right” sex are everywhere, the more often a person feels that something is wrong with them. Gloss and social media sell not only beauty but also a script: how you should look, how you should react, how long it should last, what you should be like in bed—confident, flawless, always ready. In real life, desire doesn’t work like that: it’s sensitive to fatigue, stress, relationships, and whether the body feels safe.

When we unconsciously measure ourselves against a “glossy norm”, intimacy turns into a performance. Instead of “what do I feel?”, “am I attractive enough?” and “does everything look right?” appear. In that moment, the nervous system chooses control again, not pleasure—not because you “don’t know how”, but because it’s hard for the body to open up under the gaze of the inner critic.

French sexologist Catherine Blanc often speaks about the gap between the “sexuality we’re sold” and the sexuality we actually live: alive, uneven, dependent on context and feelings. This view is helpful because it gives you your right to normal: if desire doesn’t obey scripts, it’s not a breakdown. It’s a real body, a real nervous system, and a real life.

How can self-care support intimacy without pressure?

Self-care can support sexuality when it’s about sensory comfort and care: warmth, scent, soft textures, the feeling of cleanliness and support. In that sense, everything that returns you to sensation can be helpful: a warm shower, lotion with a pleasant fragrance, soft underwear, comfortable clothing, pleasant bedding, dim light.

Self-care starts to harm when it turns into punishment: “until I lose weight, I don’t have the right to pleasure.” The guideline is simple: after care, you should feel a bit calmer and warmer toward yourself—not more anxious.

How can I talk to my partner about shame without ruining intimacy?

Body shame is often accompanied by fear: “if I say it, it will get awkward”. But silence can make it worse: tension builds up, intimacy becomes an “exam”, not a dialogue.

“I-statements” and clear, practical requests help:

- “I sometimes tense up because of body shame. Dimmer light and a slower pace help me.”

- “I need more time for cuddling—then it’s easier for me to relax.”

- “If I ask for a pause, it’s not about you. It’s a way to come back to my body.”

What’s one sentence you can say to your partner in the moment?

“Can we go a little slower for a minute? It helps me relax and feel you.”

If resentment, tension, or arguments regularly come up in your conversations, that can also affect intimacy. In this cluster, there will be a separate publication about why conflicts don’t always “end with make-up sex” and how to restore contact through conversation rather than pressure.

How can I stop thinking about how I look during sex?

The question “how do I look?” usually triggers observer mode: you’re watching yourself from the outside and judging. In that moment, the body becomes an object, not a home. The way out is not banning thoughts, but gently redirecting attention back to sensation.

Try replacing “how do I look?” with “what do I feel?” and return to one of the anchor phrases:

- “I’m allowed to be alive, not a picture.”

- “I’m coming back to sensation.”

- “My body has a right to comfort.”

When is body shame a reason to talk to a specialist?

Professional support can be appropriate if:

- shame is so strong that you avoid intimacy or relationships;

- during intimacy or after it, panic sensations hit, the body “freezes”, you feel detached or empty;

- there is an experience that still hurts, and the body responds with tension or “shutdown”;

- self-criticism sounds like inner violence, and you can’t stop it;

- there is pressure, coercion, humiliation, or intimidation in the relationship, or you’re afraid to talk about your boundaries.

In such cases, talking with a psychologist or sex therapist isn’t “only when everything is ruined”. It’s when you want to return safety, respect, and the right to pleasure.

What can I do today to make it a little easier?

- Choose one safety condition (light, pace, pause, clothing) and allow yourself to have it.

- Before intimacy, do “30 seconds in the body” and notice how tension changes.

- Say one simple sentence from the script to your partner, or write it in your notes.

- Instead of “something is wrong with me”, tell yourself: “I’m learning to come back to sensation”.

Sexuality isn’t an exam or a competition. It’s a dialogue between the body, the nervous system, and a sense of safety. And that dialogue can be restored step by step.